‘The Place’ to be?

Gemma Fraser, Improvement Lead, on community engagement and the Place Standard tool.

These past few months, I have been reading all the Community Justice Outcome Improvement Plans from across Scotland. But please don’t feel sorry for me, there is a huge amount of creative and supportive activity happening in every corner of the country that seeks to prevent offending and reduce further offending the panacea!). This is primarily through addressing the multiple and complex needs of people with offending backgrounds, their families and those harmed by crime, within our diverse but connected communities. I can honestly say, it’s all happening! We can be immensely proud of such progress towards change, in my humble opinion.

While reading the plans, I was particularly struck by the level of engagement carried out with those impacted by our justice process. This ranged from focus groups with those completing Community Payback Orders or serving custodial sentences, to one-to-one interviews with the victims of crimes and their families. It is obvious from this that people with lived experience best understand the issues posed by offending and the justice process. They have very clear views and, more often, smart solutions as to how we can improve things. Using these findings correctly can reduce our prison populations, providing sustainable community alternatives and a better future for generations to come.

How do we harness this engagement to create change? This fits in nicely with my work in Community Justice Scotland, where we seek to identify improvement opportunities; ways that we can capture real-life experience and apply analytical tools to improve services and the experiences of the people that use them. Handy really.

I have spent a large part of my career working across Local Authority community planning. While this has been largely strategic in nature (where at times my report-writing was the biggest strategic risk), I have been fortunate enough to work with local projects aimed at understanding communities, how they want to participate, and what ‘co-production’ and ‘co-design’ can mean beyond the latest buzz words.

An example of this is the Place Standard tool.

‘The Place Standard tool lets communities, public agencies, voluntary groups and others find those aspects of a place that need to be targeted to improve people’s health,

wellbeing and quality of life’

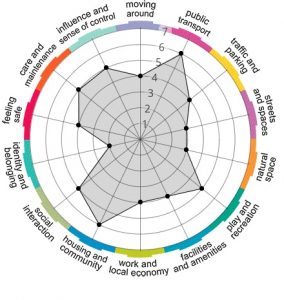

The tool considers both the social and physical environment, allowing those experiencing it to structure conversations about place and community. Fourteen questions are asked and scored between one and seven:one meaning room for improvement and seven meaning little improvement is required. Responses are plotted on the diagram, with those areas nearest the centre requiring most attention

When I place this tool in a community justice context, I can quickly identify a number of ‘places’ associated with the justice process that – while effective in their delivery – often concern the communities that use them:Nerve-wracking police custody facilities; intimidating Sheriff Court buildings; intimate social work settings ;and vast prison establishments. While the Place model could be applied to considering improvements in all these facilities, some questions would require alteration to better reflect outcomes and what communities felt they needed from them. This would move us beyond a cycle of justice interactions which, to my mind, don’t yet represent a ‘system’ of connected parts.

So how would a justice organisation engage their communities in completing a Place Standard exercise? Particularly when we know these communities are often already disengaged or not regular consulted on the ‘bigger issues’? I know we ask, but how do we show we care? The key appears to be in the provision of meaningful feedback and a true role for them in the end product.

True to form, my example of such engagement lies in Fife, The Youth Charrette. In July 2016, Fife Council facilitated a group of local young people from Glenrothes to review their town centre and consider its future. After establishing their initial views of it (largely based on them leaving it as soon as a bus arrives), and explaining the Place Standard Tool, young people were taken into the environment to consider the questions posed by the framework. The event culminated in a collective Place diagram and additional notes against each question. Young people were then asked to consider how improvements might be made and formal recommendations were presented to Council management – many of which were adopted and fed back to the group.

It is possible to take people with lived experience; those harmed by crime; families ;and partner services into places across the justice process in a similar way. There is an additional benefit to this too: it takes down the barriers felt by these groups and serves to address some of the common misunderstandings about how our justice process and its places operate. Get your local media involved!

I have always understood the reasons for positioning local community justice partnerships in a wider community planning context. For me, it is in part the ability to take advantage of tried and tested community engagement models like the Place Standard Tool. The Community Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 requires us to engage, but does leave us with a choice about how meaningful this needs to be and the means for achieving that. Good practice is everywhere and this will allow a clear feed from people using justice places into the person-centred outcomes we seek to achieve on their behalf. And I don’t believe there is anything tokenistic about that!